by Rachel Reeves

08/18/2025

Interviewing Damian Fulton is like studying one of his paintings: the first thing you notice is there’s a lot going on. He talks fluidly, articulately, and fast, pinballing ideas that span decades and genres and Southern California subcultures. Sometimes he’ll stop himself mid-sentence. “Wait,” he’ll say, “you’re not even asking any questions.”

When I do ask questions, he’ll pause to reflect, before he unspools. “Wow, good question,” he’ll say. “Wow, I don’t know. Just let me get on the couch here, doctor. I’m going to blast a little bit.”

This is how he tells stories, both in words and in paint: in blasts, with movement, with action, with verve.

“Wow, I don’t know. Just let me get on the couch here, doctor. I’m going to blast a little bit.”

Fulton paints live at the El Segundo Art Walk each year, an exercise he enjoys for the sheer challenge of trying to zone in, focus, and create something locally resonant amidst neighbors offering him beers and drunk people congratulating him.“At the Art Walk I see people I’ve known for 35 years living in this town but I only see them at the Art Walk. It’s like, how you doing, Judy, how’s the kids, and we chit chat, so it’s become like one part performance art, one part neighborhood reunion,” he said. “Painting live is a much bigger risk.”

Fulton has painted at every Art Walk, and while this year he’ll be painting live at Oceanside Museum of Art instead, he’ll still have a gallery at the Art Walk featuring original art that hasn’t been seen before, as well as other paintings and prints. There will also be a raffle, the winner of which will take home an original painting.“I want to do the Art Walk forever,” he said. “I’m proud of what our town has done to put art on the map. [The Art Walk] is really, really special.”

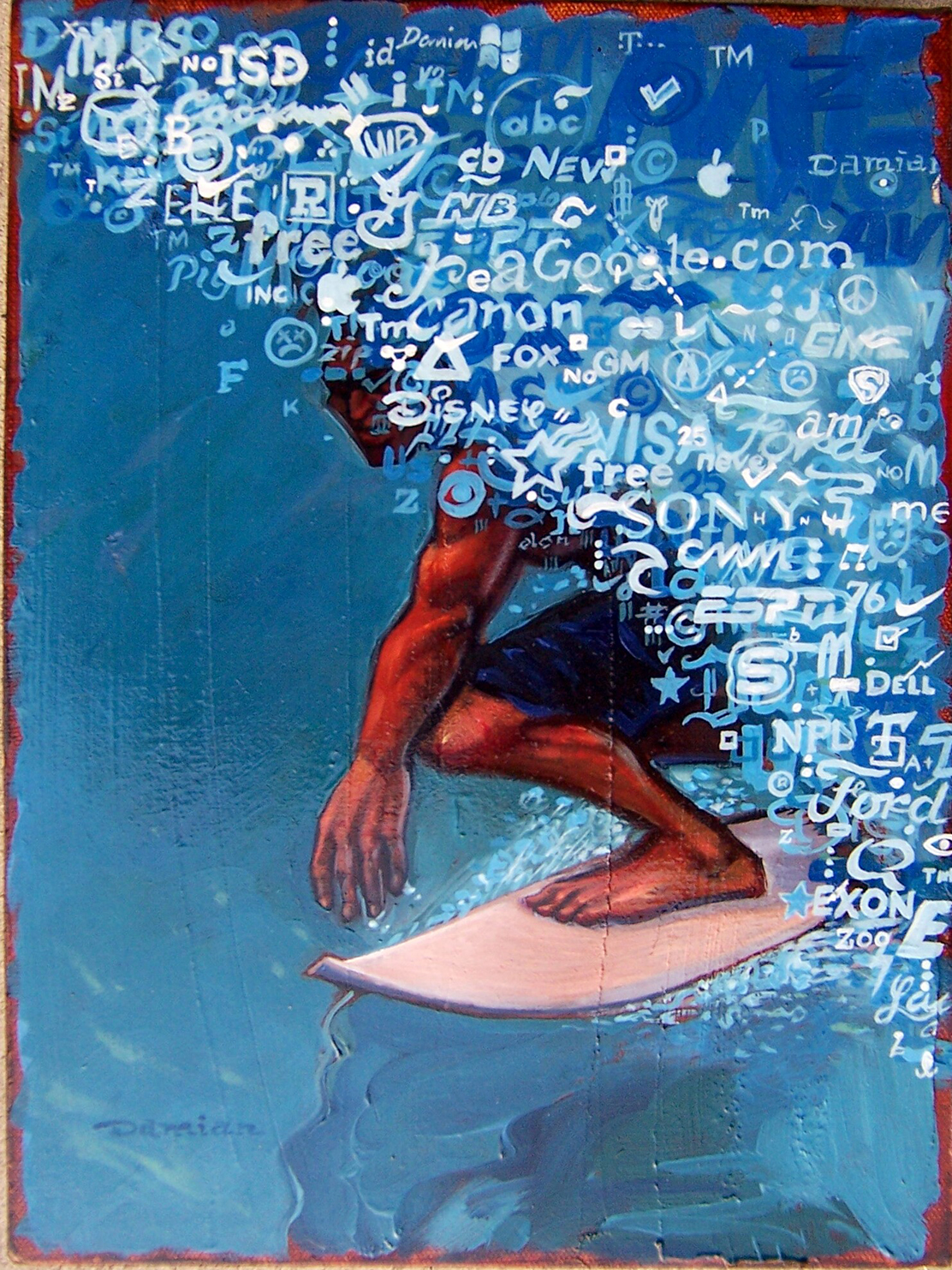

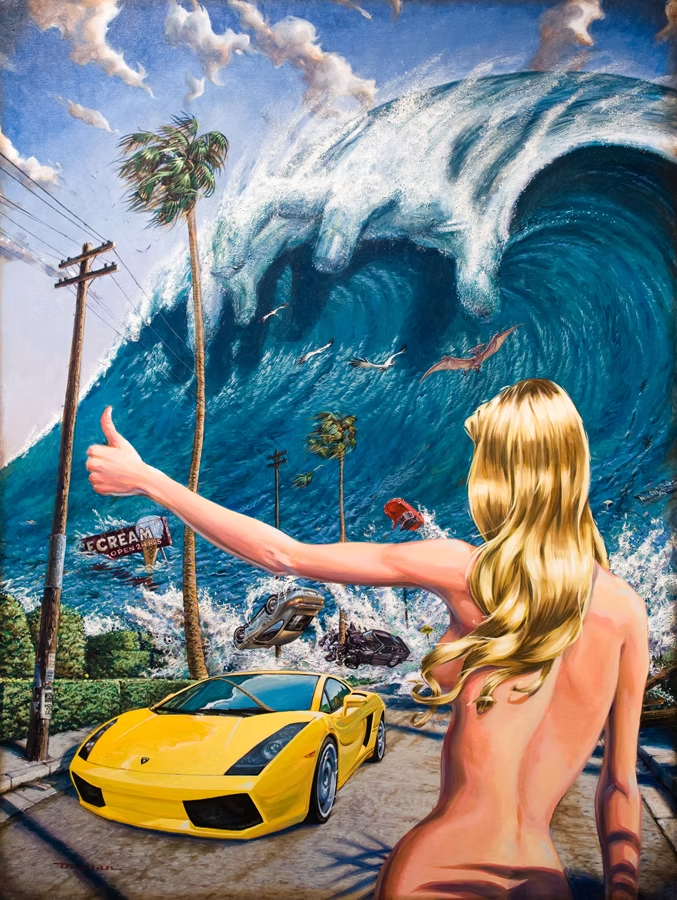

Fulton is not the kind of artist who paints precisely what he sees. Instead he tells elaborate, highly interpretable stories about the motorcycle, car, and surf cultures of the coast that incubated him and the fantastical, imagined worlds he entered through comic books and horror films. The header of his CV distills his interests into three words: “Wheels, Waves, Wonder.”

“I’m proud of what our town has done to put art on the map. [The Art Walk] is really, really special.”

Fulton’s work features scenes from the film of his life: Looney Tunes he grew up watching in black and white on Saturday mornings; characters that roamed Disneyland, the park where he and his brother would ride their bikes; outlaws and hot rodders and “cool bad guys” he grew up admiring beneath the Huntington Pier; superheroes he worked with as vice president of creative development at Marvel; tattooed surfers who crowd the line-up at El Porto, not far from the El Segundo home where he and his wife, Alisa, raised their four kids and still live.

He wants viewers to be as perplexed by one of his paintings as they might by a painting from the Dutch Golden Age—an image of a skull growing vines, for example—or by the chaotic cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the Beatles’ eighth studio album. He’s inspired by other painters who tell rich, winding stories: Howard Pyle, NC Wyeth, Norman Rockwell.

“It’s just that I would rather have a little bit of involvement from the audience,” he says from his studio, where he spends most of his time these days. “I want the casual viewer who walks by to look and gaze for a second and kind of try to unfurl what all this stuff is, what this symbolism is, and make up their own mind.”

His illustrations, which appear on billboards, bodies, buildings, and canvases all over the world, seem to move. They feel more like experience than observation.“I like action,” Fulton said. “There’s something about, you know, the peak moment of an animation. They call it the extreme. You want to catch the moment not in between a stride, where someone’s walking, because otherwise the feet are together, and it doesn’t look like they’re walking. You want to get the full extension. I’ve always been attracted to the big moment.”

As a kid, he didn’t draw Batman posing; he drew Batman punching the Joker in the face. Drawing the big moment was his way of assuming some control in a world dominated by adults.

“You’re a little kid and the adults rule everything,” he says. “But on a piece of paper, you can master anything. You can achieve anything.”

Fulton spent his childhood drawing. He grew up in a suburb of Irvine, surrounded by orange groves, strawberry fields, and what he called “a bunch of free-range kids.”

“We might as well have been in Oklahoma,” he said. “I mean, it really had nothing to do with LA.”

He drew characters from the monster movie reruns that looped on the three channels available on TV. He drew Superman and Frankenstein and the Wolf Man. He drew what he catalogued mentally as he rode his bike with his brother 10 miles to the beach to bodyboard and surf. They’d stay until sundown, recycling bottles for coins to buy deep-fried tortilla strips from the snack shack, and then they’d return home, biking an hour through traffic and smog and gangs back to their sleepy little town.

Under the pier at Huntington Beach, he became steeped in the subcultures that run like throughlines up the Southern California coast. He encountered the rebels, the hot rodders, the gangsters, the bikers, the surfers. It was a whole new world. He loved it.

At school, teachers noticed his artistic gift. They told him he’d see his name in lights one day. He never forgot it. He internalized that praise as pressure, which he credits for the risks he’s taken: painting live for an audience, for example, or murals that consume entire buildings, or canvases reflecting both technical precision and winding narrative. When someone tells you you can, you’re more likely to try.In high school, Fulton kept drawing: cartoons for the school paper and yearbook, a comic book, T-shirts for friends. He went on to study art at Cal State Fullerton, but found the theory uninspiring.

“But on a piece of paper, you can master anything. You can achieve anything.”

College did, however, yield a cartoon that would explode in popularity. After classes, Fulton and some friends would mess around on urban assault bikes in prohibited places. One of the guys he rode with, a writer and photographer for BMX PLUS! Magazine, offered to connect him to the publication’s editors.

When BMX PLUS! rejected his sketches, Fulton went back to the drawing board, conceptualizing something different: Radical Rick, a BMX rider who slayed the dragons and got the girls and would quickly amass a devoted following, winding up tattooed on bodies and optioned for a Hollywood film, which is still under development. This year marks the 45th year of Radical Rick.

In 1984, Fulton, his wife, and their first baby moved to LA so he could take a job at advertising company Ogilvy & Mather. There, according to his CV, he “cut his teeth in advertising playing with toys.” He designed campaigns for Hot Wheels, Barbie, and He-Man, then moved on to campaigns for such brands as Kraft, BP, Hilton, Chevron, Pepsi, Carl’s Jr., Toyota, and Elton John.

He won some of the most prestigious awards in his field–Cannes Lion, D&AD, Gold Pencil–for his work as a creative director. He also did stints as vice president of development at Marvel and senior designer for Disney.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Fulton worked on his last campaign, promotion for the movie “How to Train Your Dragon” that would appear at Universal Studios in Beijing, China.

“And I remember I was really at my wit’s end,” he said. “I had, you know, prostituted myself. I was a young guy who drew and painted because I loved to. And then I departed from that and went into selling … and I had always sort of longed for that time when I drew as a kid for the sheer purpose of joy and entertainment.”

After four decades in advertising, he found that when he sat before a blank canvas, he didn’t know what to do. But if a friend or client asked him to do something, he would deliver, on deadline. Creativity is a muscle that does what it’s trained to do. “So I retired, like, I quit,” he said. “But I just could not launch. I could not launch. And every time I said I’m going to paint canvases, someone would call and I’d go, okay, you have a problem, I solve problems, I can solve that problem for you. Canvases, paint, everything just went to the side. So this is a behavior that I’ve practiced. I’m really good at avoiding stepping into what I believe I’m really meant to do, what I want to do.”

But Fulton is on the precipice of a new season. He’s giving himself five years to become a “true studio artist” who produces consistent work for galleries and museums. When other students go back to school, Fulton will, too.

“And I remember I was really at my wit’s end,...”

“I realized: what if I gave myself an assignment? What if I set the boundaries of the assignment?” he said, giddy about the idea. He chose work he loves and, with help from ChatGPT, reverse-engineered a curriculum focused on how to make it.

Starting in September, he’s going back to school for four hours a day, four days a week, in his studio, except that he’s the teacher and also the only student.

“I’m going to spend a lot more time practicing the things that I haven’t practiced since art school,” he said. “Every day I have an assignment to fulfill. I even wrote into the curriculum, you know, stand up and have a break after two hours, do some push-ups, have a drink of water, walk around.”

Creativity, it turns out, is a lot like getting to the surf: when there are barriers to what you want, you have to be intentional about overcoming them. This is a major theme in Fulton’s personal work, not surfing, exactly, but getting there.

As a kid, he biked 10 miles in traffic to reach the beach. When he moved to El Segundo, distance was no longer an impediment to surfing; now it was the relentlessness of meetings, deadlines, and keeping four kids housed, fed, schooled, and entertained. It was also the crowds.

“You move to LA and you go, wow, it’s way more dense, way more diverse, just so much more complicated,” Fulton said. “Surfing has kind of always been a little territorial, but I never experienced it like I experienced it here. Here it’s gnarly. I mean, there’s just so many people competing.”

In a painting called “Gold Rush,” a group of characters is racing frenetically toward the beach. They are as wild and weird as any of his characters: an ephemeral baby, a mohawked surfer wearing a gas mask, floating mermaids, a horned businessman carrying a briefcase and a devil’s trident, a donkey with human arms, a robot with the glass-encased face of a clown. All are reaching, with some palpable desperation, toward a perfect, silky-smooth barrel breaking off Manhattan Beach Pier.

In “Cacophany in Sea Major,” Fulton depicts the chaos of a crowded line-up. Two buff men are punching each other in the surf, surrounded by a crocodile skeleton, a snake, and pieces of a broken surfboard. A girl in a red Baywatch suit paddles into a wave populated by surfers taking off, surfers wiping out, surfers nosediving, surfers cutting other surfers off. There are lost boards, oil drums, and people falling out of the sky. A surfer with the gnarled face of Red Skull, the Marvel character, claws at the subject of the painting, who’s entering the fracas on a surfboard. “Invitation to Folly and Wisdom,” backgrounded by the familiar red-and-white-striped smokestacks of the El Segundo refinery, shows a young female surfer sashaying down the stairs to the beach through a gritty mess: fanged snakes, a scarecrow dreaming of a crow, a donkey drinking a cup of take-out coffee, a flying insect with four bulging eyeballs.

It is this nexus, this intersection of urbanness, with its cultures and subcultures and pop culture, and the ocean, forever the domain of the wild and free, that interests Fulton most.

“I don’t know what it is, but I feel such a connection to where the water meets the land,” he said. “Not just going surfing – that’s not what I’m talking about.” He’s talking instead about what the coast means, and has meant to generations of adventurers and freedom-seekers. For Fulton, who’s lived in El Segundo for the majority of his life, the coast means he’s home.

“You know, we’ve talked about cashing out and going to Tennessee or going someplace else, but man,” he said, “I sure like the weather. I sure like the beach. It’d be really, really, really hard to leave here.”

See Damian Fulton's pop-up art gallery during the Art Walk at Alex Abod Realty on the corner of Grand Ave. and Richmond St.

On Saturday, August 23th, El Segundo opens its doors for studio tours, fine art and music.

FacebookInstagramX